“Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But, it is, perhaps the end of the beginning.” English Prime Minister Winston Churchill uttered those words on November 10, 1942, in a speech at The Lord Mayor’s Luncheon in London. There were two key reasons for his newfound optimism. British armed forces had just completed a rout of the Germans in North Africa , at the now famous Second Battle of El Alamein. The Germans had been pushed out of Egypt, and the vital Suez Canal remained safely in English hands. The Prime Minister’s enthusiasm also sprang from the fact that a huge American force had landed just two days prior, in three separate locations along the northwest coast of Africa, in an undertaking code-named Operation Torch. From the Torch landings, the Americans would launch out across the desert in an eastward direction across the northern rim of Africa. The Allied plan was very straightforward, and seemed highly likely to succeed. The retreating German Army in North Africa would be trapped and destroyed. As the British pursued their fleeing enemy from Egypt westward, they would eventually push them directly into American units moving toward the east out of Morocco and Algeria. The trap was set.

In retrospect, Churchill’s exuberance at that Tuesday luncheon in November may have been a bit premature. But, three months later, in early February of 1943, exactly 75 years ago, there was reason for a guarded, and growing, optimism among the Allies. It was beginning to feel like the “end of the beginning.” There would still be over two more years of difficult and deadly fighting ahead, both with the Nazis in Africa and Europe and with the Japanese in the Pacific. The tide, however, was now definitely shifting.

As the noose tightened around the neck of the Germans in North Africa, there were promising signs appearing on battlefronts all across the globe. Most Americans know little, if any, about World War II on the Eastern Front. In late June of 1941, almost six months before America entered the war following Pearl Harbor, Hitler broke a treaty with Russia and treacherously invaded the Communist land to his east. Germany coveted the oil fields and rich farmlands of western Russia. By the end of the war, fighting on the Eastern Front would involve a combined total of almost 8 million combatants from both sides. The suffering and death experienced by both armies, as well as the civilian populace, was horrific, simply unimaginable.

While the Germans had initially made incredible gains and occupied vast areas of the Soviet Union, their advances had ground to a halt during the winter of 1942-43. Bitter weather, long, treacherous supply lines, and passionate resistance by Russians fighting for their families and homeland made the German soldier’s existence there a living hell. The worst news that any member of the German armed forces could hear was that he was being transferred to the Eastern Front. By February of 1943, the seemingly invincible Nazi war machine was disintegrating, a thousand miles from home, on the frozen fields of Russia. As hard as it is for those of us who grew up during the Cold War to fathom, vast amounts of material support from America were critical in bolstering the Soviet war effort during World War II. The tide was rapidly and decisively turning against the Nazis on the Eastern Front.

While the Russians were tying up and destroying a significant portion of the German military, British and American bombers were now beginning to systematically carry out bombing missions, from England, across the continent of Europe. By mid-1940, essentially all of the European continent had succumbed to either German occupation or control. As the Nazis solidified their grip on their neighbors, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the Baltic Sea, down to the Mediterranean Sea, and across to the Russian front, the entire continent came to be known as Fortress Europe. The Allied strategic bombing campaign, although fraught with extreme danger for the air crews involved, was now beginning to significantly impact the German capacity to wage war. Production facilities, oil refineries, military bases and airfields, and basically anything that could aid the Nazi war effort were targeted. During February 1943, U-boat (submarine) bases and associated construction facilities were designated as priority targets.

The obvious reason for giving precedence to U-boat sites was that the Battle for the Atlantic was still raging. This epic struggle consisted primarily of German U-boats attempting to sink Allied cargo ships, which were continually ferrying supplies and equipment from America for use on the battlefields of Africa, Europe, and Russia. Initial losses of merchant shipping had been staggering. Although they were still at unacceptably high levels during February of 1943, the tide was now slowly turning here as well. New technology and better methods were making the life of a German sailor serving on a U-boat more dangerous with every passing day. The hunter was now increasingly becoming the hunted.

Out in the Pacific, the war with Japan was taking on an “end of the beginning” feel as well. On February 9, U.S. forces on the bitterly contested piece of real estate known as Guadalcanal made a startling discovery. The Japanese were gone, their last troops evacuated under cover of darkness two days earlier. The long and deadly campaign for this remote and inhospitable island in the Solomon chain, northeast of Australia, was over. The United States Marines and Navy, aided at the end by the Army, had outlasted their fanatical foe in this brutal six month struggle. It is all but impossible to overstate the depth of suffering and privation experienced by those who fought for Guadalcanal, American and Japanese alike. To the Japanese, the “Canal” came to be known as “starvation island,” more dying from starvation and disease than the thousands who died there in actual combat. Legendary Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey later paid solemn tribute to those who served in America’s first offensive in the Pacific, “Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific.” It may have saved Australia as well, and definitely turned the tide of the war in the Pacific. Americans were now already teaming up with their Australian allies to move further north and push the Japanese out of New Guinea. Many say the fighting there was some of the harshest faced by soldiers anywhere during the entire course of World War II.

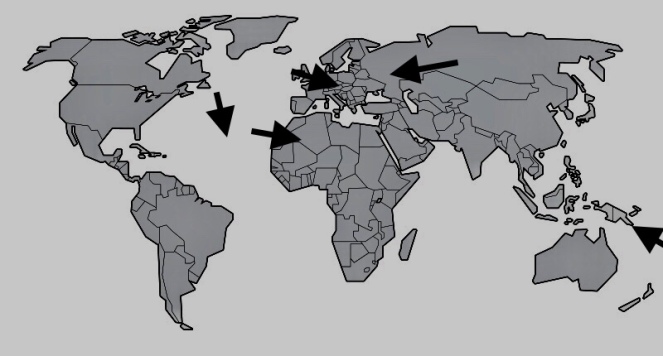

Allied Advances- February 1943

Back in North Africa, what Allied commanders had hoped would take about one month, the defeat of the German army on the African continent, had now stretched to three months. Resupplied from Sicily, the Germans were bottled up but holding on in Tunisia, and planning for a major counter-offensive. Bolstered with a naive bravado from the relative ease of their victorious landings back in November, the raw, inexperienced American soldiers in western Tunisia were now lackadaisically preparing to fight the Germans. Scattered throughout their ranks were certain key, but weak, leaders, who had not adequately prepared them for their forthcoming hour of reckoning. These ineffective commanders would be replaced, but not before a terrible price had been paid.

The Germans, on the other hand, were still a crafty and battle-hardened foe, led by the legendary “Desert Fox,” Field Marshall Erwin Rommel. In mid-February of 1943, the Germans unleashed a powerful attack on the unsuspecting Americans in the Battle of Kasserine Pass. American losses of men and equipment would be catastrophic, making it one of the worst defeats in American military history. Although technically a German tactical victory, American reinforcements would arrive, hold on tenaciously, and cause the German offensive to simply run out of steam.

Many valuable lessons were learned at the ill-fated Battle of Kasserine Pass, as well as over the next three months of combat with the Germans in Tunisia. American troops learned quickly how to fight. Officers who were unable to effectively lead in combat were replaced. Those who remained would experience a sharp learning curve in the employment of effective tactics and leadership skills. Names that are now legendary would emerge, names like Dwight David Eisenhower, George Patton, and Omar Bradley. These men, and others, would lead America and her allies to ultimate victory in Europe in the years ahead. The U.S. Army learned to fight in the crucible of North Africa. Although an essentially unknown phase of World War II today, let us never forget the North African campaign and the brave men who fought and learned there….75 years ago.

“If we forget what we did, we won’t know who we are.” Ronald Reagan